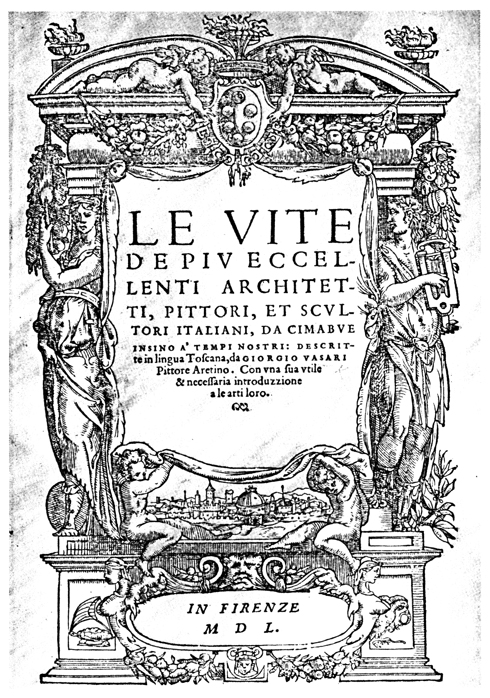

Giorgio Vasari's "Lives of the Artists" Summary ("Lives of the most excellent painters, sculptors and architects"):

Giorgio Vasari (1511-74) is the Plutarch of Renaissance Italy. His "lives of the most excellent painters, sculptors and architects" ("Lives of the Artists") runs to over half a million words and some 160 biographical portraits, among them profiles of Cimabue, Leonardo, Botticelli, Raphael, Titian, and Michelangelo. In particular, he reminds us, again and again, that living, breathing human beings -- cranky and flawed and loveable and terribly ambitious -- created the immortal masterpieces that hang on our museum walls.

During the Renaissance nearly everyone seems to have been an overachiever, and even the most rugged soldier of fortune aspired to be a cultivated patron and connoisseur of the arts. At least such is the only slightly idealized vision that has fed our imaginations for centuries. Like Shakespeare or Stendhal, Goethe or Henry James, we still dream of 15th-century Italy as the land of energy, beauty, and corruption.

Giorgio Vasari -- himself an important painter of the time -- contributed to that image by establishing the modern notion of the Great Artist, the Artist as Genius. Once, he says, Pope Benedict IX -- it was actually Boniface VIII -- wanted some pictures painted for St. Peter's and sent a courtier to Giotto to ask for a drawing as a kind of sample:

Giotto, who was a most courteous man, took a sheet of paper and a brush dipped in red, pressed his arm to his side to make a compass of it, and with a turn of his hand made a circle so even in its shape and outline that it was a marvel to behold. After he had completed the circle, he said with an impudent grin to the courtier: "Here's your drawing." The courtier, thinking he was being ridiculed, replied: "Am I to have no other drawing than this one?" "It's more than sufficient," answered Giotto. "Send it along with the others and you will see whether or not I am understood."

The courtier did so, and "as a result, the pope and many of his knowledgeable courtiers realised just how far Giotto surpassed all the other painters of his time in skill."

All in all, Giorgio Vasari's finest achievement is his account of Michelangelo, with whom he was friends, and who was the only living artist included in th e 1550 edition of the Lives. In almost hagiographic pages we learn that the artist worked constantly, sometimes didn't change his clothes for days at a time, enjoyed writing madrigals and sonnets, slept little, and could remember any work of art he had ever seen. In the contract for the Pietà he actually agreed to finish the sculpture within the space of one year and promised that it would be "the most beautiful work in marble in Rome, and that no living master be able to make one as beautiful." Apparently Michelangelo had no qualms about these rather stringent terms, because they were fulfilled to the letter. Even now, the Pietà is widely regarded as the most beautiful work of sculpture in the world. e 1550 edition of the Lives. In almost hagiographic pages we learn that the artist worked constantly, sometimes didn't change his clothes for days at a time, enjoyed writing madrigals and sonnets, slept little, and could remember any work of art he had ever seen. In the contract for the Pietà he actually agreed to finish the sculpture within the space of one year and promised that it would be "the most beautiful work in marble in Rome, and that no living master be able to make one as beautiful." Apparently Michelangelo had no qualms about these rather stringent terms, because they were fulfilled to the letter. Even now, the Pietà is widely regarded as the most beautiful work of sculpture in the world.

Giorgio Vasari records many of Michelangelo's observations about art -- including his complaint that Titian couldn't draw -- and describes in detail the great master's various projects and achievements. But he also makes sure that we can picture the man in our own minds:

Michaelangelo was of medium height, broad in the shoulders but well proportioned in the rest of his body. As he grew old, he constantly wore boots fashioned from dogs' skins on his bare feet for months at a time, so that when he later wanted to remove them his skin would often peel off as well.... His face was round, the brow square and wide with seven straight furrows, and his temples jutted out some distance beyond his ears, which were rather large and stood out from his cheeks; his body in proportion to his face was rather large, his nose somewhat flattened, having been broken by a blow from Torrigiani...

In one of the prefaces to his book, Vasari theorized that Italian art had progressed through three stages: a primitive period represented by Giotto and Cimabue, an intermediate whose giants included Brunelleschi and Donatello, and finally, the crowning third, when it achieved supremacy in the work of Leonardo, Raphael, and Michelangelo. As can be readily seen, the historian tended to favor Florentine painting over any other; he also believed that draughtsmanship (disegno) provides the only firm basis for good art, while the most perfect art also needed grace or charm. And of course artists deserved to be properly paid and properly respected.

Here's a typical story: Donatello once made a life-sized head in bronze for a merchant who objected that the price was too high. The two argued and eventually took the case to Cosimo de' Medici for adjudication. The merchant maintained that Donatello had finished the work in a month or so and was consequently asking for a compensation of "over half a florin a day." Vasari continues: "Donatello considered himself grossly insulted by this remark, turned on the merchant in a rage, and told him that he was the kind of man who could ruin the fruits of a year's toil in a split second; and with that he suddenly shoved the head down on to the street where it shattered into pieces and added that the merchant had shown he was more used to bargaining for beans than for bronzes."

With impressive self-confidence, Renaissance artists regularly flouted authority, whether religious or secular. Giorgio Vasari notes that Leonardo "did a Last Supper in Milan for the Dominican friars at Santa Maria delle Grazie, a most beautiful and wondrous work in which he depicted the heads of the Apostles with such majesty and beauty that he left the head of Christ unfinished, believing that he was incapable of achieving the celestial divinity the image of Christ required." But soon, Vasari adds, the prior of the church began to hound Leonardo about the unfinished head -- and about the similarly unfinished head of Judas. So Leonardo complained to the duke of Milan, saying he didn't think he could find a model on earth for Christ, nor was he sure about his ability to finish the Judas "for he did not believe himself capable of imagining a form to depict the face of a man, who, after receiving so many favours, could have possessed a mind so wicked that he could have resolved to betray his Lord and the Creator of the World." At which point, one imagines that Leonardo paused dramatically, before continuing: "None the less, he would search for a model for this second face, but if in the end he could not find anything better, there was always the head of the prior..."

One can almost see the twinkle in the artist's eye and that hint of a Mona Lisa smile. Still, my favorite Leonardo anecdote underscores the polymath's well-known tender-heartedness: "When passing by places where birds were being sold, he would often take them out of their cages with his own hands, and after paying the seller the price that was asked of him, he would set them free in the air, restoring to them the liberty they had lost."

Nowadays, we know that some aspects of the Lives are apocryphal, but in general Vasari deserves full marks as a historian in the classic vein -- that is, as an anecdotalist and moral guide. As he writes, "the best historians have tried to show how men have acted wisely or foolishly, with prudence or with compassion and magnanimity; recognizing that history is the true mirror of life, they have not simply given a dry, factual account of what happened to this prince or that republic but have explained the opinions, counsels, decisions, and plans that lead men to successful or unsuccessful action. This is the true spirit of history, which fulfills its real purpose in making men prudent and showing them how to live, apart from the pleasure it brings in presenting past events as if they were in the present."

Certainly, most modern readers enjoy Lives of the Artists mainly for the charm of its stories and vignettes. In this respect, perhaps the finest is the life of Piero di Cosimo, who was utterly devoted to his art and for long periods stayed inside working.

For having fallen in love with painting, he cared nothing for his creature comforts and reduced himself to eating only boiled eggs which, to economize on fire, he used to cook whenever he was boiling glue, not six or eight, but fifty at a time, keeping them in a basket and eating them one by one. He would not allow his rooms to be swept; he would eat only when he felt hungry; and he would never let his garden be dug or the fruit trees pruned, but rather he let the vines grow and the shoots trail along the ground; nor were his fig trees or any others ever trimmed, but he was content to see everything run wild, like his own nature, asserting that nature's own things should be left to her to look after, and that was enough. He frequently took himself off to see animals or plants or other things that nature creates accidentally or from caprice, and he derived from these a pleasure and satisfaction that completely robbed him of his senses.... He would sometimes stop to contemplate a wall at which sick people had for ages been aiming their spittle, and there he described battles between horsemen, and the most fantastic cities, and the most extensive landscapes ever seen: and he experienced the same with the clouds in the sky. He could not stand babies crying, men coughing, bells ringing, or friars chanting; and when the rain was pouring down from the sky, he loved to watch it as it ricocheted off the roof-tops and hurtled on to the ground. He went in terror of lightning, and when the thunder roared he would wrap himself up in his cloak, shut fast the doors and windows, and crouch in a corner of the room till the storm abated.

While eccentric and even childlike, Piero nonetheless seems to have been obsessed with death,, as evidenced by a kind of carnival float he designed called "The Triumph of Death." According to Giorgio Vasari, the Triumph was a huge chariot drawn by buffaloes, black all over and painted with human bones and white crosses, and over the chariot was a huge figure of Death, with scythe in hand, and all around the chariot were a large number of covered tombs; and at all the places where the triumph halted for the chanting, these tombs opened, and from them issued figures draped in black cloth, on which were painted all the bones of a skeleton on their arms, breasts, backs, and legs; and all this, with the white standing out from the black, and with the appearance in the distance of those torch-bearers with masks that represented skulls, both back and front, and on the neck, besides seeming utterly real, struck the eye as fearsome and horrible. And the dead, at the sound of certain muffled trumpets with harsh and mournful tones, came forth from the tombs and sitting themselves upon them sang to music full of melancholy...

Piero even looked on his own end with startling originality. "He spoke ill of doctors and of apothecaries and of those who nurse the sick and cause them to die of hunger ? He praised death by public execution, saying it was splendid to go to one's end in that manner, seeing so much of the open sky and so many people, and being comforted with sweets and kind words; having the priest and the people praying for you, and going with the angels to Paradise; and he said that he was a very lucky man who quit this life at one blow." (Giorgio Vasari's "Lives of the Artists" Summary)

For all its pleasures, there are some longueurs in Vasari's Lives, usually because of its focus on accurately describing so many paintings and sculptures. Most paperback editions consequently offer only a selection from the 160 biographies and may even abridge some of these. (In this essay I have largely relied on two fine modern translations: that by George Bull for a two-volume Penguin paperback edition, and that by Julia Conaway Bondanella and Peter Bondanella for Oxford World's Classics.) Don't worry, though, since nearly any of the several translations available will offer plenty of entertaining stories: the amorous Raphael dies at 37 from a fever brought on by excessive sexual exertions; Rosso's pet Barbary ape engages in a feud with a neighboring friar over grapes; Properzia de' Rossi, in love with a recalcitrant young man, sculpts Potiphar's wife casting off her clothes in one last effort to seduce the unwilling Joseph; and many others. Still, apart from the account of Giotto and the circle, perhaps the most famous anecdote of all is that of the architect Brunelleschi and the egg. Now, it so happened that a dispute broke out over how to construct the dome for Florence's cathedral. Brunelleschi was convinced that he could do it by vaulting, while competing architects suggested less elegant solutions:

They wanted Filippo to explain his mind in detail and show his model as they had shown theirs. He was unwilling to do this, but he suggested to other masters, both the foreigners and the Florentines, that whoever could make an egg stand on end on a flat piece of marble should build the cupola, since this would show how intelligent each man was. So an egg was procured and the artists in turn tried to make it stand on end; but they were all unsuccessful. Then Filippo was asked to do so, and taking the egg graciously he cracked its bottom on the marble and made it stay upright. The others complained that they could have done as much, and laughing at them Filippo retorted that they would also have known how to vault the cupola if they had seen his models or plans. And so they resolved that Filippo should be given the task.

Once built, that cupola gave its name to the cathedral, which is commonly known as the Duomo. To this day Brunelleschi's visionary masterpiece still gleams in the Italian sunlight, the crowning symbol of Renaissance Florence. (By Ms. Michael Dirda)

From: http://bnreview.barnesandnoble.com/t5/Library-Without-Walls/Lives-of-the-Artists/ba-p/576

General introduction of Giorgio Vasari:

Giorgio Vasari (30 July 1511 – 27 June 1574) was an Italian painter, architect, writer and historian, most famous today for his Lives of the Most Excellent Painters, Sculptors, and Architects, considered the ideological foundation of art-historical writing.

Giorgio Vasari enjoyed high reputation during his lifetime and amassed a considerable fortune. In 1547, he built himself a fine house in Arezzo (now a museum honouring him), and decorated its walls and vaults with paintings. He was elected to the municipal council or priori of his native town, and finally rose to the supreme office of gonfaloniere.

In 1563, he helped found the Florence Accademia e Compagnia delle Arti del Disegno, with the Grand Duke and Michelangelo as capi of the institution and 36 artists chosen as members.

Edited by Kevin from Xiamen Romandy Art Limited.

(Xiamen Romandy Art is a professional oil paintings supplier from China. If you want to convert your photos into high quality oil paintings, or you want the masterpiece oil painting reproductions, please don's hesitate to contact with us.)

Romandy Art Website: http://www.oilpaintingcentre.com

Tags: Giorgio Vasari's "Lives of the Artists" Summary", Lives of the most excellent painters, sculptors and architects".

|